Emotive force. The heart of any Ferrari 250 is its engine, but the history of the Colombo V12 goes back a lot further. Words John Simister. Photography Paul Harmer.

What’s your favourite Ferrari? The answer is probably influenced by your age, but for this writer it has to be one from the 1960s. Narrowing that thought leads to a 250 GT (maybe in open form, such as our California Spyder cover car), maybe a 275 GTB, or perhaps a 250 LM endurance racer. You can reduce that list to one car if you like, but the thick thread that joins them is that all are powered by a version of Gioachino Colombo’s V12 engine.

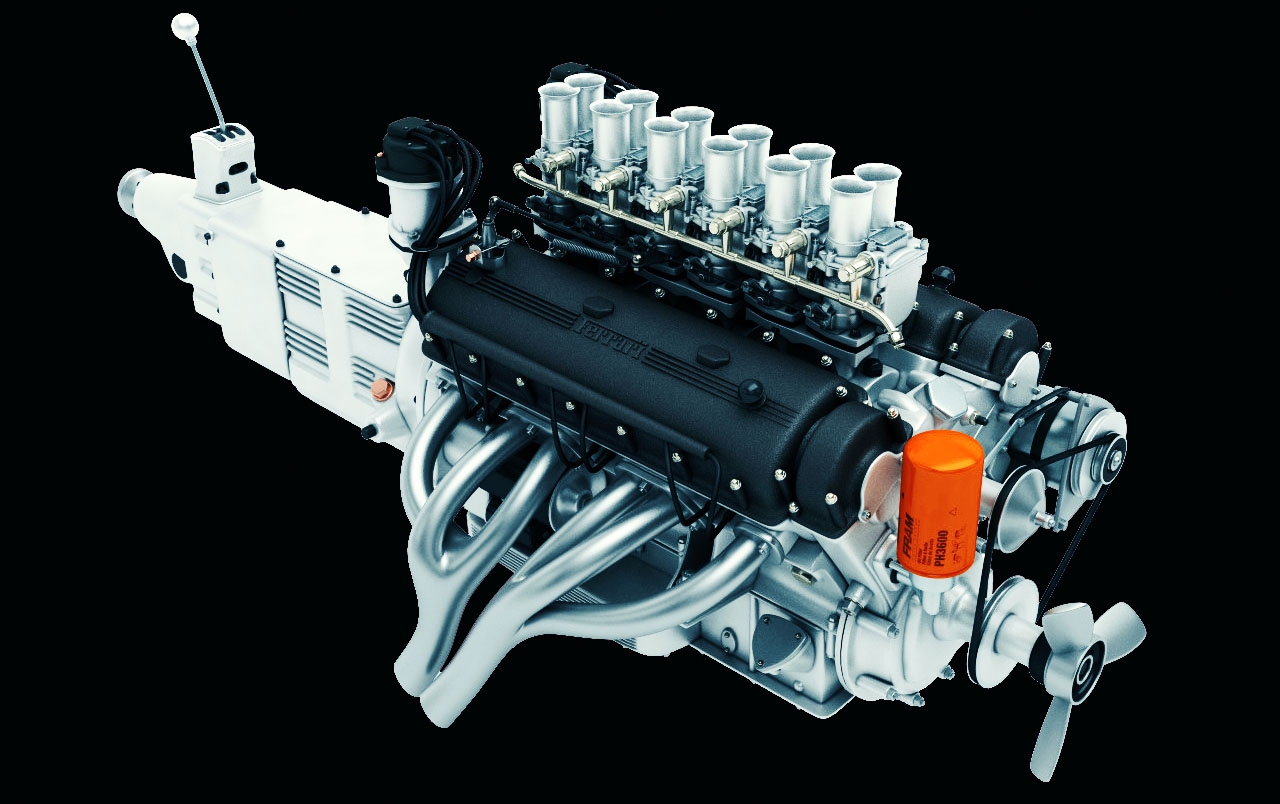

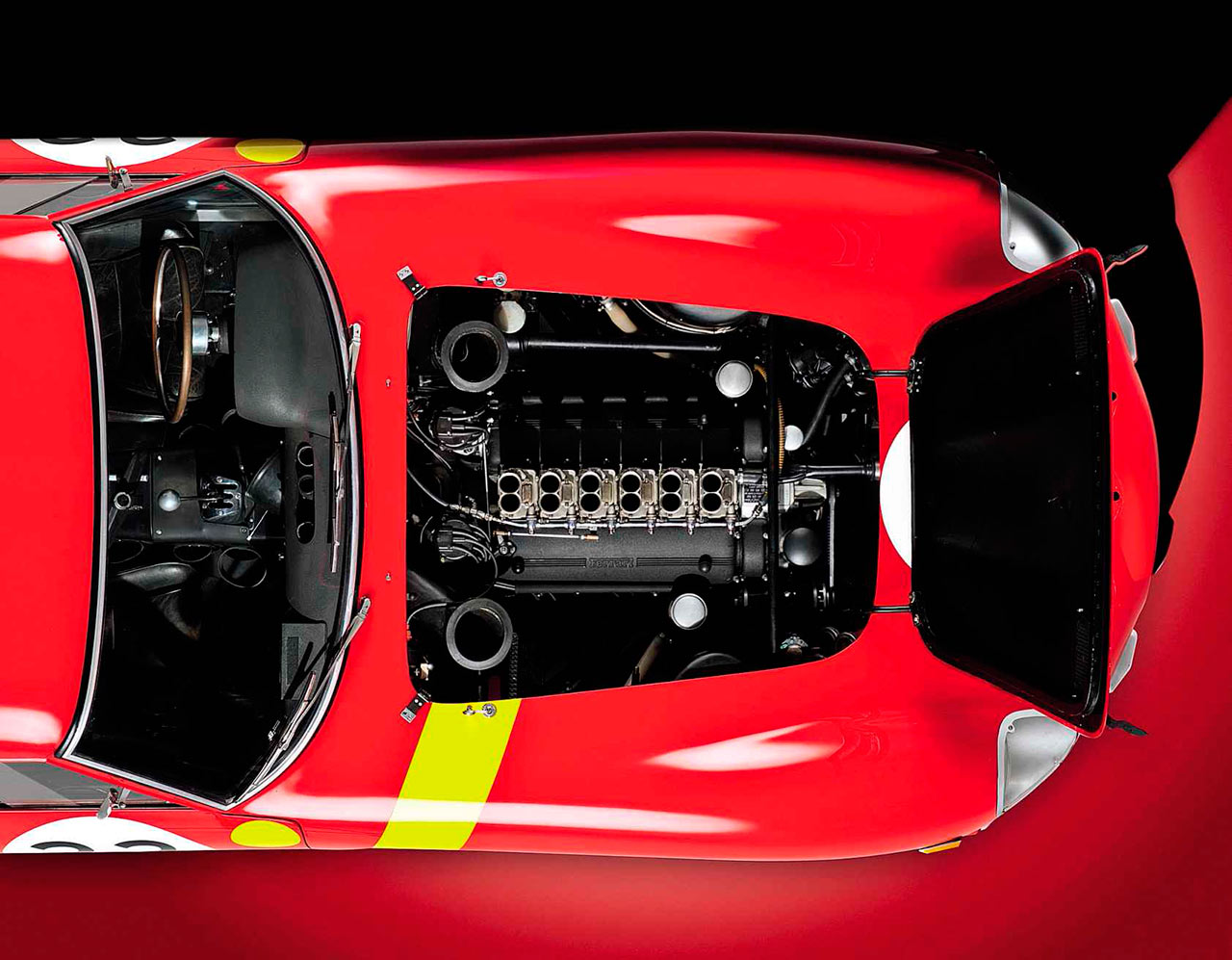

Ferrari has made several families of V12 over the decades, but the lodestone of the breed has to be this one. Its lifespan, from 1946 to (in greatly modified form) 1989, bookends that of the other great V12 from Ferrari’s earlier years, the larger-capacity range designed by Aurelio Lampredi, but in the end the Colombo-derived unit actually levelled with its former sibling’s largest cylinder dispacement. Every single Ferrari 250 bar the Europa was powered by a Colombo V12, the Europa instead relying on a downsized 3.0-litre version of the Lampredi engine. There’s substance to Colombo’s V12 as well as glamour. As well as being muscular, tuneful and handsome – check out the ridged camshaft covers, the stereo oil fillers, the finned aluminium sump, the phalanx of carburettors – it’s a tough old thing.

‘These are strong, powerful engines that go on for ever and ever,’ says James Cottingham of DK Engineering, a company well-versed in maintaining them for road and race. ‘With an Aston Martin engine or a Jaguar XK it’s all about what upgrades you’ve done to them, but with the Colombo engine we do very little to deviate from the original specification. Mostly we leave them as they were.’

That says a lot for the design of an engine that began at just 1.5 litres and grew to over three times that capacity, with just one major dimensional change to the cylinder block casting on the way. The start of the story was revealed to the world in 1946, in the nose of Enzo Ferrari’s first car to bear his name. Colombo and Ferrari had collaborated since 1929, Enzo running the factory Alfa Romeo race team, Gioachino the protegé of Vittorio Jano who designed the Alfa 8C engine (and a lot more, over the years). So the protegé was a natural choice in the new, post-war world to create Ferrari’s first in-house engine.

And what a fine engine it was, its 1496cc distributed between 12 tiny, oversquare cylinders each of (almost) 125cc to give that first Ferrari its name: 125S. The two banks of six cylinders were set in a 60º vee for perfect mechanical balance. It produced 100bhp and revved to a racy 7000rpm. These, for 1946, were remarkable figures.

Why so many cylinders, with all the friction and complexity they create? Partly it was to keep reciprocating masses low, which allowed high revs and therefore high power for the size of the engine. Such a configuration is guaranteed to make a great noise, too, which must have appealed to Enzo. The V12 design was his favourite. ‘When I began,’ he wrote in Caratteristiche Tecniche dei Motori Ferrari realizzati dal 1946 al 1985, ‘against everyone’s advice I wanted a 12-cylinder engine and that engine, which many people expected to put an end to my ambitions, is still recognisable in its numerous sons and grandsons. I have tried them all, eight-, six- and fourcylinder units, but I keep returning to the 12-cylinder, which remains my favourite.’

Colombo’s first of the breed certainly approached the state of the engine designer’s art at the time. Its block and heads were of silumin (silicon-aluminium). The ‘nitrogenised’ crankshaft had seven main bearings and was machined from a steel billet. The combustion chambers were hemispherical. The camshafts sat on top.

The valves in these chambers were not, however, actuated by separate inlet and exhaust camshafts in the classical overhead-cam, hemi-head way, despite the large angle between their stems. Each bank had just one camshaft, driven by a stout triple-row chain and acting on opposed rockers: one row of six for the inlet valves, the opposing row for the exhaust valves. These pivoted not on a pair of rocker shafts but within their own aluminium housings. Each housing held one pair of opposed rockers, both of which contacted the camshaft via rollers, as well as forming a bearing cap for the camshaft.

As originally designed, the engine had its spark plugs on the carburettor side of the cylinder heads. That was fine when there were just three twin-choke downdraught Webers, or even the single twin-choke instrument deemed sufficient for those Ferraris – 1948’s 166 Inter was one – that cantered rather than pranced. But when the need for more power led to six densely-packed twin-chokes, it was clear that access to the plugs would be impossible.

So new cylinder heads were designed, with spark plugs on the exhaust-port side, and with this redesign the engine lost its ‘hairpin’ valve springs (two per valve) and the smaller versions that sprung the rockers. The loss of this Colombo-ism was slightly sad, given that such springs were the best solution for 1940s metallurgy.

Ferrari’s 50 Years of Innovations in Technology by Karl Ludvigsen explains why. The spring pressure was achieved by bending the wire of the spring instead of twisting it, which gave a more consistent closing force. The main mass of the spring was not attached to the valve stem, which reduced reciprocating forces, and the springs’ compactness allowed shorter, lighter valves. Sounds good; but metallurgy moved on (as did Colombo, to Alfa Romeo), and conventional coil springs did the job instead.

The rationale for this redesign became evident on the arrival in 1957 of the Ferrari Testa Rossa, whose cracklered camshaft covers – still each with two balls by which to pull them off, provided the gaskets hadn’t stuck too hard – signified the automotive power milestone of 100bhp per litre. Or nearly; actually it produced 290bhp from its 2953 cc, helped by its six Weber 38 DCN carburettors, but to quibble would spoil the story. Other changes for an engine now up to nearly 250cc per cylinder, thus meriting the 250 designation, included proper head gaskets instead of copper rings, more head studs and bigger main bearings.

As it turned out, the cylinder heads now resembled those of the larger Lampredi engine apart from one major difference. The larger unit’s wet cylinder liners were, rather unusually, screwed into the cylinder heads, which certainly overcame any head-sealing problems but gave top-end overhaul an added battle with piston-ring compressors. Not that Lampredi was directly involved in the redesign; he’d left Ferrari for Fiat in 1955, five years after Colombo’s departure. Jano was still around to watch over things, though.

Those new heads were a key point in the Colombo engine’s evolution. Two more followed. Amazingly, even the 3.3-litre 275 models still used broadly the same shallow, wet-liner block as the original 125, its lower edge level with the crankshaft axis unlike the deeper-block Lampredi engine. As, of course, did the 159, 166, 195, 212, 225 and 250 in between, all except the first two using the same 58.8mm stroke. This expandability is why the engine had stayed in production for so long, but it also ensured that a 3.3-litre 275 engine was very oversquare indeed.

To make it any larger now called for a bigger block. The 1960 400 Superamerica, whose designation referred to the 4.0-litre capacity and should really have been called 330, stretched the original block to its absolute limit, so when the 330 size reappeared in 1963 it was with a bigger block using wider bore spacing.

Then came, in 1967, twin-cam heads for the 275 GTB4, the number suffix denoting the four camshafts. Meanwhile the bigger block of the 330 had grown further to a nominal 365cc per cylinder, or a 4390cc total, and in 1968 it gained twin-cam heads for the 365 GTB4, known better as the Daytona.

By now there was barely anything left of Colombo’s original design, but the line of descent was still clear. What was originally the ‘small’ Ferrari V12 had surpassed the capacity of the early Lampredi engines, and in one uniquely big-blocked variant had exactly matched the capacity of the final Lampredi motor, that of the 4962cc Ferrari 410 Superamerica built from 1955 to 1959. This uniquely large-lung Colombo was found in 1964’s 500 Superfast, its capacity the largest ever achieved by the Colombo family.

Such ample swept volume was not approached again until the 400 saloon was announced in 1976, with 4823cc to rush it across continents. By now the stroke was up to 78mm – 10mm longer than the Superfast’s – and there it remained for the final incarnation of the Colombo line, the 4943cc 412 of 1986.

That iteration lasted until 1989, relaxing gently in the shadow of the upstart flat-12 (despite the name, not a boxer but more a 180º V12), and then quietly faded away as the Colombo thread finally wore through. Three years later Ferrari launched the 456 with a brand new, 65º V12, and there has been such an engine ever since.

But still the sturdy Colombo engines live on, as does the engineer’s spirit in those smaller-block, two-cam units that best represent the way he designed it. James Cottingham again: ‘We may slightly improve the camshaft profile or use a more modern piston design. We’ll use modern chains, bearings and gaskets because there’s no reason not to, and we’ll fit oil seals on the valve stems. But that’s all. There’s no need for performance upgrades. They’re perfect as they are.’

‘There’s substance to Colombo’s V12 as well as glamour: muscular, tuneful, handsome – and it’s a tough old thing’