Brabham, Bernie, and a garage owners Great Formula One Adventure. Not content with simply running Hexagon of Highgate, Paul Michaels decided to go motor racing, too. Richard Heseltine tells his story. Photography Lyndon McNeil/LAT.

Were it to happen today, the story would be distilled into an attention-grabbing soundbite. Imagine something along the lines of ‘London dealer takes fight to F1 elite’ and you wouldn’t be far off. The thing is, nowadays the idea of an enthusiastic motor trader joining the Grand Prix circus seems improbable. It just wouldn’t happen given the government-sized budgets required to compete in motor racing’s upper echelon. Scroll back 40 years, however, and, for one season only, British Racing Brown rocked as Goldie Hexagon Racing proved that inexperience doesn’t equate to inability.

“I must have been mad,” laughs former team principal Paul Michaels, who made the leap from histories to the international stage in 1974. “I was a lot younger then, of course, but at the time it didn’t seem that brave a decision to do Formula One. It was still possible for someone like me to run as a privateer. I’ve always loved motor cars and motor sport. It was just something I really wanted to do.”

“My father was in the motor business,” he continues. “He started off in Cricklewood before moving to Leighton Buzzard and I remember him bringing home all these different cars. From day one, I knew precisely what I wanted to do in life. I founded the business in 1964 and started messing about with cars.” Which is something of an understatement, Hexagon of Highgate swiftly taking on all manner of marque agencies: “It was a lot easier back then. You could simply phone up a manufacturer and ask, ‘Can I be your distributor?’ Most of the time the answer would be ‘yes’.

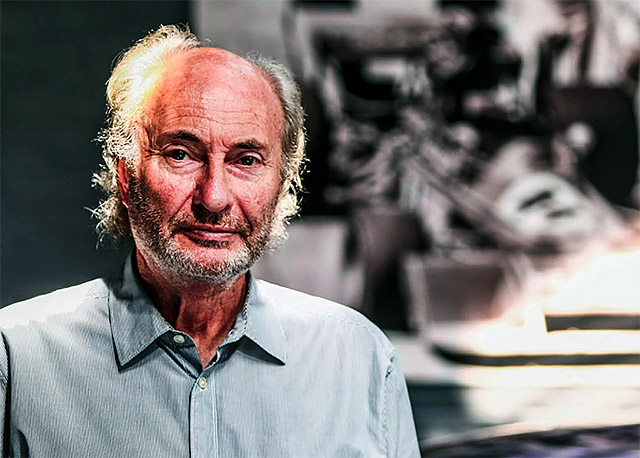

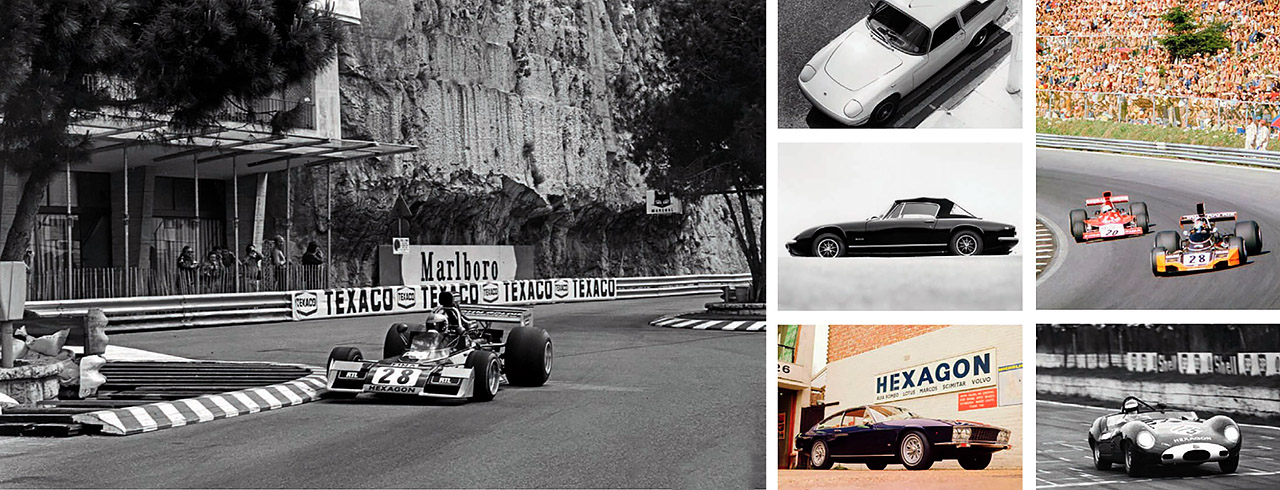

Paul Michaels today, in his London showroom (top). Far right, from top: Watson on his way to fourth position in the 1974 Austrian GP; Marshall in Hexagon Lister.

Watson at Monaco in 1974. Below: Michaels came up with the Lotus ‘Elanbulance’ and +2 convertible; Monteverdi on the Hexagon forecourt.

These days you have to jump through flaming hoops. Over time, we had Alfa Romeo, Lotus, Reliant, Marcos, BMW-all sorts.” Hexagon did a few projects of its own, too. The Lotus ‘Elanbulance’ was perhaps the most memorable: “That was my idea. I loved Elans, and I had a baby so I decided I needed a more spacious estate version. Specialised Mouldings of Huntingdon did all the glassfibre work. I was pleased with the way it turned out so we began offering the conversion in 1971. I fully expected it to do well. It didn’t; we made two. We also did a convertible version of the Elan +2 but I think that was even less successful. From memory, we made only one of those.”

Another diversion was the UK Monteverdi concession: “I’m not sure whether they approached us or we approached them, but Peter Monteverdi flew to London and we shook on a deal. I’ve read that he could be volatile, but I found him pleasant enough. We had a 375L, which looked beautiful but it wasn’t as good a car as it might have been, and the early 1970s wasn’t the right time to be selling something so thirsty. We soon went our separate ways.”

There was always motor sport: “Historic racing in the early 1970s was very different to how it is now. These days, it’s all about huge transporters and motorhomes. Back then, it was club racing. We started out with an ex-Ecurie Ecosse Jaguar D-type. We initially ran Mike Franey, but he failed to turn up for a race so we gave his seat to Nick Faure. I then acquired other cars. There was a Maserati Tipo 61 ‘Birdcage’ and a Lister-Jaguar in which Gerry Marshall won the last-ever race at Crystal Palace in 1972 – but we stepped up to ‘modems’ after I traded a Bugatti for a March 721 The March had a chequered history, having briefly been fielded in F1 wearing a bizarre Luigi Colani-designed body. The Eiffeland-March was then sold via Bernie Ecclestone to Tony ‘Monkey’ Brown. The Dubliner in turn returned the car to its original configuration prior to doing the deal with Michaels. With the car came some spares. That, and a driver: John Watson. In what was basically a one-off exercise, Michaels ran the future Grand Prix victor at Brands I latch for the October 1972 John Player Challenge Trophy. ‘ Wattie’ came home sixth overall.

The car was sold shortly thereafter, Hexagon returning to histories as Watson embarked on his nascent Formula One career, only for a leg- breaking crash in the Race of Champions to end play. “To begin with, I enjoyed historic racing, but it started to get a bit political,” Michaels recalls. “It got to the point where it was no longer fun, so I decided to look more seriously at contemporary racing and bought a Trojan T101 to do the 1973 Rothmans F5000 series.

“I needed a driver and hired Willie Green, who had impressed me greatly in histories. For whatever reason, we didn’t have the best of seasons and, towards the end of the year, we organised a test day at Silverstone. John was more or less fit to come back following his big accident, so I asked him to give the car a shake- down. ‘Wattie’ got below the lap record so we put him in the Trojan for the last few races.” The Belfast-born hotshoe finished on the podium in the championship finale at Brands.

And, just as night follows day, thoughts naturally turned to Formula One. “It wasn’t that big a leap when you think about it,” insists Michaels. “There wasn’t that much difference between F5000 and F1, at least in terms of machinery.

I did the sums and it seemed do-able. I managed to get a chap called John Goldie to come in with us; he was a property man who had made a lot of money in France. We went to see Bernie Ecclestone, who then owned Brabham, and did a deal for a used BT42. The plan was for us to switch to a new BT44 part-way through the year, and John would be our driver.”

Operating out of a workshop adjacent to the Highgate showroom, the equipe’s toe-in-the- water run in the 1973 British GP as a sponsor led to full immersion the following season as an entrant: “When we got the BT42, it was just a bare monocoque and some bits, so there were a few all-nighters getting it ready. During the first round in Argentina, John wasn’t happy with the handling. We couldn’t work out what the problem was until (chief engineer) Alan McCall did a torque test. The car had clearly been shunted at some point and all the rivets were loose.

“At Monaco we got a point for sixth, John finishing between Emerson Fittipaldi and Graham Hill. We were then invited to the palace because we had finished in the points. I was there after the race, armed with the equivalent of the Yellow Pages trying to find a hire shop so we could rent some dinner jackets.

Michaels, with Hexagon’s David Hipperson mid-crash. Below, from top: Bell in Penske, 1976 and (bottom) 1977; glamorous launch for ‘Wattie’ and Brabham.

Michaels, with Hexagon’s David Hipperson mid-crash. Below, from top: Bell in Penske, 1976 and (bottom) 1977; glamorous launch for ‘Wattie’ and Brabham.

“John then had a great result in Austria (fourth place) and he qualified on the second row at Monza. Unfortunately, an upright broke on the slowing-down lap and we had no spares. Bernie loaned us a BT42 for the race but John fell down the order because there hadn’t been time to set the car up. He finished seventh. That was our big opportunity, although we did get some more points for fifth in the US GP at Watkins Glen.”

Inevitably, success came at a price: “In Formula One back then, there was a pecking order for tyres. As privateers in our first season, we were nobodies until we started getting points. Firestone took an interest, but this was at a time when the works Brabham team was aligned with Goodyear. I expect pressure was exerted on Bernie – as much as pressure can be exerted on Bernie – that it wasn’t good for us on Firestones to be mixing it with the factory cars on Goodyears. There wasn’t any nastiness, but there were delays in getting spares and things like that.

“In addition, Goldie backed out part-way through the year so I funded the last third of die season myself. I tried desperately to raise money to carry on in 1975, and came close to a deal with Gitanes to sponsor a two-car team running John and Jean-Pierre Beltoise, but at the end of the year I decided to stop. I had to be pragmatic. That season totalled £114,000, and it would probably have been about twice that in 1975.”

Not that Hexagon was completely done with Formula One, if only at ShellSport British Group 8 level, with Derek Bell winning the 1977 Oulton Park Gold Cup aboard Michaels’ Penske PC3. “Actually, we did return to ‘proper’ F1, if you like, because we ran Boy Hajye in the Dutch GP at Zandvoort in 1976,” he says. “’That was a one-off thing, though. What pleases me is that while we were in Formula One, we kept getting better. We improved right to the end, and having a driver like John made all the difference.

“These days, there’s no hiding place for drivers: it’s all there in the telemetry. Back then, you had a pad and a pencil so you relied on the guy behind the wheel. They could say all sorts of things if a race didn’t go their way – blame the car or the team. There was none of that with John. He was very serious about his racing, focused on the job in hand and we relied on him totally.

‘WE KEPT IMPROVING, AND HAVING A DRIVER LIKE WATSON MADE ALL THE DIFFERENCE’

Hexagon occasionally ran other drivers, including Brian Henton, Damien Magee – who lived up to his nickname ‘Mad Dog’ – and Bell, of course, but John was miles better than any of them. We did one race (the 1974 French GP with a second BT42) and two tests with Carlos Pace, who was a nice guy but he had no idea about set-up. He just drove around problems. That’s a skill, but it doesn’t help in the long run.”

Save for sporadic returns to historic racing – most recently in 2012 with his ex-Ecurie Endeavour Aston Martin DB4GT- motor sport is now a thing of the past for Michaels.

As indeed is selling new cars: “It got to the point that I wasn’t having fun anymore. If we sold a car, three hours would then be spent working through finance agreements. I had kept my hand in with the old stuff, and simply decided to concentrate on that instead. I have done since the end of 2013 via Hexagon Classics.”

Looking back isn’t really Michaels’ thing, at least not without a degree of prompting, but he clearly relished his time at motor sport’s top table. If nothing else, it led to a lifelong friendship with ‘Wattie’: “I don’t think a week goes by when I don’t speak to John, and I’m grateful for that. Ours was among the last privateer teams to ever have success in Formula One, and I like to think that we punched above our weight.” That it did, and more.