“The Hesketh and I did two-and-a-half back ward Somersaults 30ft in the air” Ian Ashley recalls the moment that ended his F1 career, but, as he tells Richard Heseltine, that didn’t put him off racing – even if some of his mounts were a bit ropey. Portrait Tony Baker, Archive Ian Ashley/Richard Heseltine/LAT.

Ian Ashley looks back at his long and multifarious career in motorsport. Crashley’s career Racer Ian Ashley on life at the wheel.

Outlining a life less ordinary by means of detour and digression, Ian Ashley is on a roll. Conversation ricochets back and forth, punctuated only by protracted bouts of mirth. One minute he’s discussing why the Stanley-BRM P201B Formula One car was half-decent despite its status as a dud, the next he’s describing how and why he found himself flying floatplanes in Alaska. Should you ever meet this born raconteur, be prepared to cancel the rest of your day because the stories just tumble.

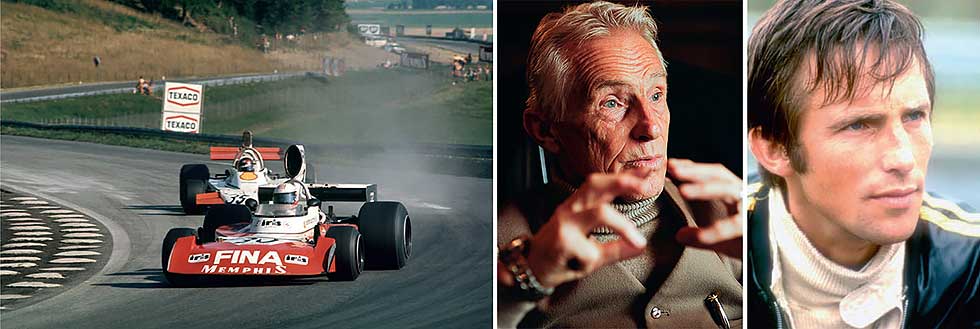

Nevertheless, there is one question that begs to be asked, and it might sully the sunshine mood. Our host is already two steps ahead. “I’m guessing you want to know about the origins of my nickname,” he says, matter-of-factly. Yes, that would be it: “James Hunt and I were friendly rivals. We moved through the ranks together. Neither of us had many races under our belts by the time we arrived in Formula Three, which was a major category back then. We did a lot of learning in public and there were one or two incidents. It was all part of our education. We were both very young, blisteringly fast and stuck out like sore thumbs. Mike Ticehurst, a mutual friend, coined us ‘Crashley ’n’ Shunt’ and it stuck. The thing is, I drove many terrible cars, or hopped into something without any prior testing, and things broke. As such, it wasn’t always my fault!” And with that, the infectious laugh returns.

Warming to the theme, he adds: “I did rather scrape the barrel with some of the cars I raced, didn’t I? You go where the drives are, though, don’t you? Funnily enough, I didn’t have any great ambition to be a big-time driver when I started out. I just knew that I wanted to race. In July 1966, I went to the Jim Russell racing school, which was my father’s way of proving to me that it was all a fatuous idea and therefore I should finance it myself. I defied his expectations and claimed pole position for my first school race and won by a clear minute. Simultaneously, my grannies bought me a £200 ‘Frogeye’ Sprite in which I won a handicap race at Mallory Park and obtained signatures for my licence. I was still only in my teens, don’t forget. Then, for ’1967, a friend purchased a Merlyn F3 car on tick. We did eight international races, which culminated in the opportunity of a works seat with Merlyn for ’1968. Better still, I also received an offer from Graham Warner’s Chequered Flag team.”

The ‘Tattered Rag’ had hitherto fielded umpteen young aces on their way to stardom: “Grahamand his wife Shirley were really supportive. It was an honour to be chosen to drive the quasi-works F3 McLarens with backing from Scalextric. Mike Walker was the number one driver and he won first time out at Oulton Park. My car wouldn’t even start! The M4A was very heavy but could have been good had we been able to develop it further. Unfortunately, [associate sponsor] Esso abruptly pulled out of racing, which meant there was a big hole in the budget. For ’1969, it was a step down to Formula Ford with a factory Alexis. Then there was a works Lotus drive for the 1970 Brazilian Temporada series, which was a great adventure. I finished second behind my dear friend Emerson Fittipaldi.”

Yet it was in Formula 5000 that Ashley made his mark. Following a few outings towards the end of ’1969 with a Kitchener K3, his stock soared aboard successive Lolas. Then came Formula One, sort of: “In August 1974, I had just finished an F5000 race at Brands Hatch driving for Jackie Epstein’s Shell Sport/Radio-Luxembourg team when someone from Token approached my friend/manager Mike Smith about a possible drive in the RJ02 for the German Grand Prix. Following a quick chat with Graham Warner and [oil trader] Richard Oaten, who were involved financially, I agreed to do it so long as I could test beforehand. The Tuesday before the race, I did maybe 12 laps at Goodwood.

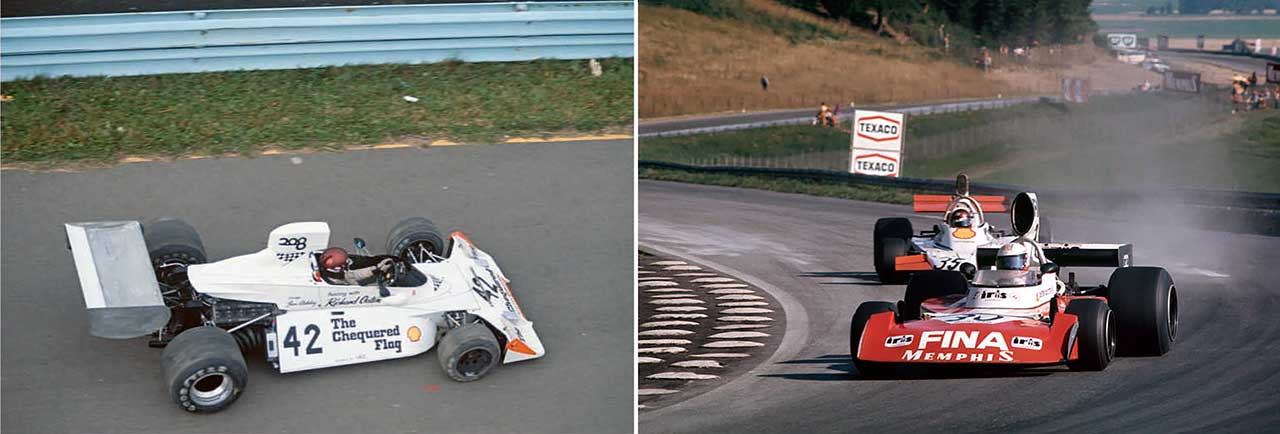

“At the Nürburgring, the right-front tyre deflated at the bottom of the Foxhole during first practice. In second practice, a mechanic mistakenly installed the wrong top gear so, instead of having 11,000rpm, I had only 9000. I qualified on the back row alongside Derek Bell in his Surtees, but, just before the warm-up lap, [the car’s designer] Ray Jessop told me to lift off at the Foxhole, what with all the extra race fuel on board. I did just that but the right-front tyre blew again anyway at precisely the same spot. I continued for another 10 miles, arriving at the pits minus the tyre and the right-front wing. Ray was concerned that vibrations may have cracked the top wishbone so he changed it in record time, eyeballing the camber and toe-in settings. There was no replacement wing so they simply taped up the wing support to keep it in place, increased the left-front wing and reduced the rear wing. Ray then wished me luck.”

Our hero finished 14th following another identical puncture, the issue in time being traced to a batch of porous wheels: “For the next race, the Austrian GP at the Österreichring, there was only the one flat. I was doing 180mph-plus at the end of the pit straight heading into the flat-out right-hander at the time. In the race, a left-front tyre began bubbling: the front wings were flexing at high speed and this reduced grip, which overheated the inside tread. Ray then called me in for a two-minute pitstop. Then my left-rear wheel came loose. In I came again. While they replaced it, the engine began to overheat. They thought the car was on fire and hauled me out, only to realise that it was just steam. I clambered back in and off I went to finish eight laps down [on winner Carlos Reutemann].”

Then came salvation, of a kind: “Graham and Richard were losing patience with Token and did a deal to purchase an ex-John Watson/Hexagon Brabham BT42. They did this without my knowledge. That was wonderful, but then John Surtees phoned and invited me to Goodwood for a test. There was a possible drive going. I didn’t get out on track until late afternoon and did one lap before returning to the pits on seven cylinders. Nevertheless, John phoned me the following day and offered me the seat for the rest of the season – Monza, Mosport and Watkins Glen. I asked for two days to decide because I was contractually tied to Epstein for F5000.

Not only that, I didn’t know what to say to Graham, who’d bought the Brabham specifically to keep me in F1. I knew I’d do well in the Oulton Park International Gold Cup in the F5000 Lola T330 [he won], and the Brabham was potentially a good car, so I phoned Surtees and declined his offer. It’s fair to say that he wasn’t impressed.

“The Brabham was a total bitsa, though, and I failed to qualify for the Canadian or US Grands Prix. Looking back, I probably should have gone with Surtees but then the fella who took the drive [Helmuth Koinigg] had brake failure at the Glen, crashed through the Armco and was decapitated. There but for the grace of God…”

Following a cataclysmic mechanical – and leg – breakage at the ’Ring with Williams in 1975, which in turn destabilised his F5000 campaign, Ashley was forced to decline an offer from Team Lotus to replace Jacky Ickx for the five races that rounded out the year. The following year began with Stanley-BRM, only for the team to withdraw following the Brazilian GP opener. Back in F3 for ’77, Ashley returned to the top table with Hesketh Racing at the tail-end of the season. It would prove a maddening experience, one that came to an abrupt halt at Mosport.

“Going over the hump at the end of the back straight, the nose section collapsed,” he recalls. “The 308E and I did two-and-a-half backward somersaults 30ft in the air, flying over the Armco before demolishing an unmanned TV platform. The car then buried itself 10 inches into the ground, which crushed my ankles. When I came to, I was full of morphine. Emerson, his personal surgeon, Jochen Mass and the mechanics were cutting me out with small hacksaw blades, with Mike Wilds behind me gripping a plasma bag.” Having also sustained two shattered wrists, it marked the end of the F1 adventure. Not that he is embittered, just irked: “What upset me more than anything was that nobody from Hesketh seemed interested in what had happened or even bothered to visit me in hospital.”

Ashley then embarked on a new career: “My father had been the deputy chief test pilot on Concorde, but I had no real interest in following his lead until I spent a week with a TWA stewardess who asked me what I planned to do next.

I had no idea because I was still recuperating. She suggested I train ‘as a pilot or something’.” He subsequently became a Learjet captain based out of New York, flying the great and the good including an incredulous Jackie Stewart – “I recall him saying: ‘Where’s the real pilot?’” – but the lure of motor racing was never far away.

Following an eight-year sabbatical, Ashley returned to the cockpit in Indy Car: “Emerson persuaded me to have a look. He said it was just like F5000. I came back in November ’1985 for the final round in Miami and qualified ahead of the likes of Michael Andretti and Kevin Cogan. I did a few more races, but couldn’t put a deal together.

Then, at the end of 1987, I was persuaded to race a friend’s motorcycle at a wet club meeting. I won and that was all it took. I competed across the USA. Upon watching a video of Steve Webster And Tony Hewitt winning the World Grand Prix Sidecar championship, however, I returned to Britain in 1990 determined to do some Grands Prix, even if they were on three wheels! I was successful, too. I then became aware of what was going on in the British Touring Car Championship. I did the ’93 season, but my 1990 Vauxhall Cavalier was outdated and the wrong car to have, although I finished third in the privateer class.”

More recently, Ashley has been a front-runner in historics, and not just on four wheels. “You know,” he concludes. “I should have made it in F1 like my contemporaries, but I’m still here and having a wonderful time racing. Right now, I’m probably enjoying it more than I did in the ’70s.” Hemay be in his 70th year, but the commitment hasn’t slackened. Nor has the speed. Ashley doesn’t lift for anything, it seems.

Clockwise, from left: a thoughtful Ashley, but the smile is never far away; he was a major force in F5000, here at Brands, November 1973; Ashley’s tenure with Stanley-BRM in ’1976 proved brief – the team contested only a single round of the F1 World Championship. From top: youthful Ashley in a McLaren F3 car ahead of ’1968 season, enjoying a joke with mentor Graham Warner who would later fund him (briefly) in F1 – team-mate Mike Walker is in the foreground; Ashley came third to Bob Evans in ’1974 F5000 Championship.

From top: Ashley aboard problematic Token RJ02 chasing the Surtees of Dieter Quester at the Österreichring in the ’1974 Austrian Grand Prix – the Token would suffer a flat at 180mph; “total bitsa” Brabham failed to qualify for that year’s US GP.

“I SHOULD HAVE GONE WITH SURTEES, BUT THE FELLA WHO TOOK THE DRIVE WAS KILLED”

From top: Ashley is now happier at his work, but no less competitive, here at 2009 Silverstone Classic; practice for ’1977 Austrian GP; ’1987 Miami GP during Indy Car comeback; Ashley finished third in privateer class of ’1993 BTCC, but he wasn’t struck on tintops.

‘WHAT UPSET ME MOST WAS THAT NOBODY FROM HESKETH EVEN BOTHERED TO VISIT ME’