LIFE CYCLE THE LIFE STORY OF A BMW E3

Hugh’s German bosses in 1974 told him to buy an expensive car that would impress clients – he chose this BMW 3.0S E3.

Hugh and his son Charles used the BMW to drive to a wedding at the Schloss Tratzberg in Austria in 1998.

1974 Hugh Cantlie buys a new E3 BMW 3.0S in Munich for £4000 Hugh Cantlie arrived in Germany in April 1974 as a quantity surveyor for British property firm MEPC. As part of his job overseeing a shopping centre project in Munich he had to make the 240-mile commute to the Frankfurt head office for meetings every week.

‘My bosses told me I needed to get a car,’ says Hugh, ‘preferably an expensive one – something that would show clients how important we were. They wanted me to get a Jaguar, but I thought it would have forever been in the garage.’

And besides, he already had a relationship with high-class German cars from his army days. He says, ‘Four of us clubbed together £35 to buy a Mercedes from the Black Watch transport sergeant while I was stationed in Germany. It was a big car and had done time on the Russian Front as a staff car so we called it Adolf. Anyway, we paid him the cash, he threw in a jerry can of fuel and off we went.’

The Mercedes made it as far as the officers’ mess before the back axle fell off, so it remained parked up there and performed all manner of shady functions. In the meantime, Hugh’s experience of cars built by a rapidly recovering Germany was expanding. ‘A BMW 327 cabriolet caught my eye soon after the Mercedes,’ he says. ‘That was a former staff car too but it was in much better condition and it served me really well – I used to go to polo matches and on summer holidays in it. Then a 328 caught my eye – I really admired the flushfitting headlights and it drove really well.’

So it was no wonder that Hugh declined his senior management’s offer of a Jaguar. Instead he visited BMW’s central Munich dealership where he found a mid-blue E3 3.0-litre S saloon looking every inch the modern executive express. ‘It was big and looked very upright,’ he recalls. ‘I loved the design and the instruments.’

The 3.0-litre sat in the middle of a line-up of models that ran from 2.5 to 3.3 litres. Hugh’s car-to-be had a four-speed manual gearbox, front seatbelts, a gold velour interior and a large sunroof. It also came with a hefty asking price – £4000.

Hugh had to address one serious flaw almost immediately. ‘I opened the sunroof practically the first day I took it out,’ he says, ‘and my hair got all tousled. It turned out to be a design fault so I sent it back to have a wind deflector fitted.’

Grooming crisis averted, Hugh decided to drive the 100 miles or so to St Anton Am Arlberg for a spot of end-of-season skiing. He chose to go via the daunting 5718ft Flexenpass, which is famous for its galleried avalanche tunnels set into the rock. He smiles as he remembers driving into a snowstorm, confident that the BMW would see him safely through it. ‘All of a sudden it began to slide,’ he says, his hand snaking across the table by way of demonstration.

‘A little opposite lock and less right foot calmed things down a little but conditions worsened the higher I climbed, and the lights seemed to be getting dimmer. It was snowing really hard by this point and I could hardly see where I was going, which was worrying because there were huge trucks coming the other way.

‘Eventually I stopped, thinking that the battery was dying and found that the headlights were caked with mud. I cleaned them off and they shone perfectly.’

The E3 – now named Bertha after the World War One German heavy howitzer – quickly settled into its routine of drives around Munich and Frankfurt and proved that the autobahn was its natural habitat. Then another diversion from work – this time a shooting trip – took the pair to Hungary where, somewhere in the triangle of borders between Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, thick fog began to close in.

‘We drove on and on until at last we came to a checkpoint manned by armed guards (these were still the days of the Cold War), but no one seemed to know where I should go next. Even the machine-gunner came down from the watchtower and joined in the debate.’

Eventually they sent Hugh and his flashy capitalist ride off in the direction of Veszprém to the north of Lake Balaton. However, by now some 400 miles into his journey, Hugh needed to find somewhere to stay for the night. The first hotel he encountered was hosting a raucous local farmers’ shindig, but he stayed anyway – only to find full directions to where he was supposed to be going in the back pocket of his trousers the next day.

The Austrian border guards proved to be sticklers for the rules when Hugh and his friends rolled up on their way to one of their favourite lunch stops – the Golden Stag Inn near Salzburg. The BMW was a roomy four-seater but the guards pointed out that Hugh’s car was actually carrying five people. They eventually relented and let Hugh through the checkpoint on condition that he wouldn’t let it happen again. But of course it would – they would have to drive back the same way later that night.

On the drive back home, Hugh could think of only one option – someone would have to recross the border in Bertha’s spacious carpeted boot and that someone was Hugh’s friend Pamela. ‘She’s still a close friend,’ he says. ‘I think she’s forgiven me!’

Rather less forgiving was the chief of police Hugh encountered at a border crossing into Liechtenstein. He took exception to the BMW’s exhaust note – repeated encounters with mountain passes and exposure to snow and road grit had left it sounding noisy and rough. ‘He told me I couldn’t enter because the BMW’s racket would frighten the cows,’ says Hugh.

‘I pleaded to be allowed in just this once because I was on my way to an important meeting in Zurich, but one of the guards pointed out that I’d promised them I would fix the noisy exhaust – caused by a split manifold – only the previous week. I finally convinced them to let me through on condition that I went straight to a garage to get the exhaust attended to.’

When Hugh asked where he could possibly get the work done at such short notice, the guards informed him that there was a BMW garage in Vaduz. ‘I was worried that it wouldn’t be up to the job,’ Hugh says, ‘but I needn’t have worried – the mechanics specialised in building BMW racing engines so they certainly knew their way around the road cars.’

Hugh later discovered that the garage was also a Jaguar agent. He says, ‘I asked one of the mechanics how he coped with handling such poor-quality cars and he told me that Jaguars were great designs that just weren’t put together very well. He said that they took them apart and put them back together properly so they were every bit as good as their designers had intended. ‘Then he told me that I could collect the BMW two days later, leaving Liechtenstein’s cows to graze in peace once more.’

The cows of Bavaria, on the other hand, were an entirely different matter. ‘Not long after getting the new manifold fitted I was driving home from the Golden Stag between two big maize fields when this huge cow ambled out into the road in front of me,’ he says. ‘There was no way I could avoid it – the BMW thumped it hard in the back and it sat heavily on the front wing. ‘After a moment or two, it slowly gathered itself up, emptied the contents of its bowels on to the by now rather crumpled wing and wandered off.

‘When I rang our company solicitor to report it, he said, “Don’t wash the crap off, whatever you do” – I presume he viewed it as evidence – so we had to drive back to Munich with it in that state. In the end we had to leave it like that for a week, so it was rather crusty by the time it went back to the factory for repair.’

‘A cow ambled into the road. I couldn’t avoid hitting it so it sat on the wing, crumpling it, then emptied its bowels on to it before getting up and wandering off’

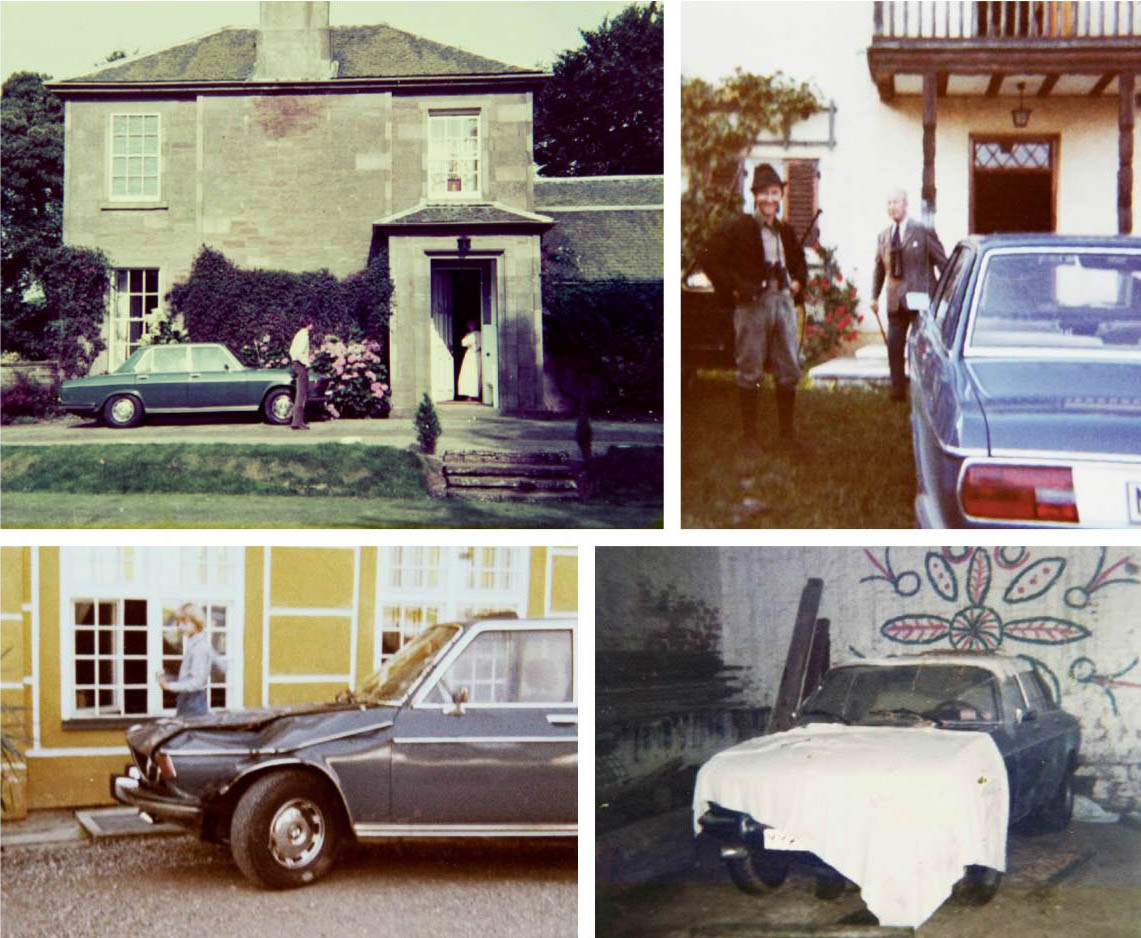

Hugh’s second BMW – a 328 – pictured with a Hungarian friend at a horse show near Düsseldorf, 1954. Hugh’s son Charles engrossed in rooftop map-reading near Passchendaele, 1976. Charles and the E3 – now proudly wearing its new British registration number – en route to a holiday in Austria, 1981. Body repairs and a repaint recaptured the BMW’s youth.

Visiting friends in Coupar Angus in 1979, the year after Hugh brought the BMW back to the UK. Clearly delighted with his new car – and suitably attired – while staying with friends in rural Bavaria, 1974. The aftermath of an errant cow sitting on – and manuring – the front wing near Winhoring, Bavaria, in 1975. Taking temporary shelter in a friend’s Gloucestershire barn during a house move, 1982.

1978 Hugh Cantlie brings the BMW 3.0S back to the UK When the time came for Hugh to return to England in 1978 the BMW was as fit and able as the day he first drove it out of the showroom. But wasn’t it time for a change? Hugh smiles and shakes his head. ‘The thought never crossed my mind,’ he says. ‘It had served me well and faithfully, so I took it back to the UK with me.

‘At the time there were only one or two 2002s on British roads so people weren’t used to seeing any kind of BMW, let alone an E3. I used her all the time I lived in London – which was probably rather silly because of the narrow streets and heavy traffic – but she was such a great car to drive. I had a very good chap to look after her who had a garage at the end of a mews in South Kensington.’

That was just as well, because life in the city soon began to take its toll on the BMW – Hugh’s mechanic eventually had to replace its aluminium cylinder head after it became what Hugh describes as ‘terminally aggravated’ by the endless stop-start traffic. In 1983 Hugh decided it wasn’t a good idea to drive such a big car in the capital and invested in ‘a Fiat something-or-other’. Four years later he moved to the Cotswolds, where the BMW spent its winters tucked away in a barn – but not before Hugh had taken a few simple precautions. ‘I always topped up the anti-freeze, disconnected the battery and put her on jacks to save the tyres,’ he says.

Even so, it became clear that Bertha was in need of refurbishment so Hugh sent it to Oakey’s in Oxfordshire to have rot in the lower front doors cut out, and a full respray. ‘It needed rear springs and dampers too,’ says Hugh, ‘but that was a result of me regularly loading it with wine crates from a good vineyard in Alsace-Lorraine’.

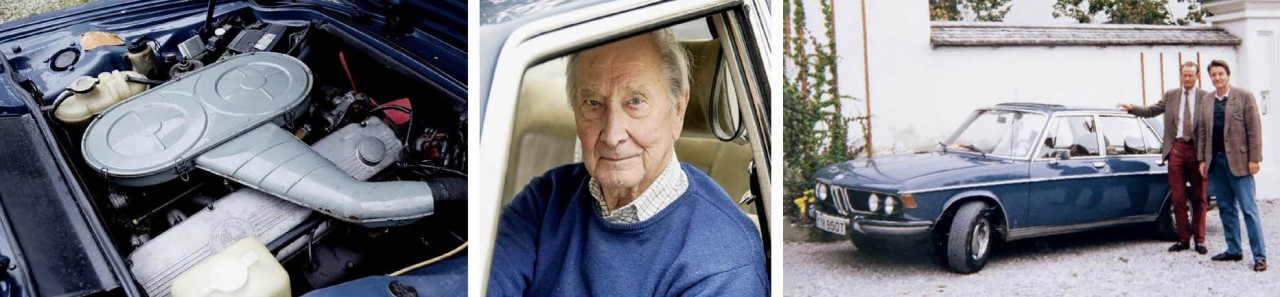

With the BMW now back to full health, Hugh still regularly drives it in an autobahn state of mind. Recently he overtook three cars on a Northumbrian dual carriageway and was pulled over by a police car. When the officer asked if he knew what speed he had been doing, Hugh assured him that he didn’t. Taking a long, hard look at the sleek Seventies BMW with the distinguished ex-guards officer behind the wheel, he asked, ‘How long have you had the car?’ When Hugh replied, ‘Forty-two years,’ the officer shook his head and said, ‘Well, bugger off and don’t do it again.’

After more than four decades with his beloved car, it seems unlikely that Hugh will be having any more roadside conversations with lenient police officers – he’s decided the time has come for Bertha to go to a new home. If you’re interestetded you can contact Hugh at [email protected].

BMW’s dual nationality clear from its British and German international registration letter plates.

Hugh’s BMW is finally up for sale after 42 years of continuous ownership. 3.0-litre BMW M30 engine didn’t take kindly to London’s stop-start traffic – its aluminium cylinder head had to be replaced in the early Eighties.