Tiger’s return to Le Mans. Can the Sunbeam Lister prototype complete its mission after 50 years? Mission: Le Mans. The Lister Tiger prototype only made it to the test day 50 years ago, says Julian Balme, but could the Sunbeam do any better at the Classic?

The mission appeared to be straightforward on paper – take the prototype Le Mans Sunbeam Tiger back to France 50 years after its first appearance there and complete the Classic. The only trouble was, La Sarthe hadn’t been kind to the venerable Coventry firm and its V8-powered sports car – though back in the summer of 1964 the vast majority of its problems were of its own making.

Rootes had always possessed a keen competition department, though, tellingly, throughout the 1950s it had enjoyed far greater success in rallying. At the time, Le Mans was the race every enthusiast was aware of, not least because of the similarity between a number of its contestants’ vehicles and those found in the local showroom. It was therefore logical that any ambitious sports car manufacturer should have some form of presence in the 24-hour marathon – hence the first works foray with the Sunbeam Alpine in 1961.

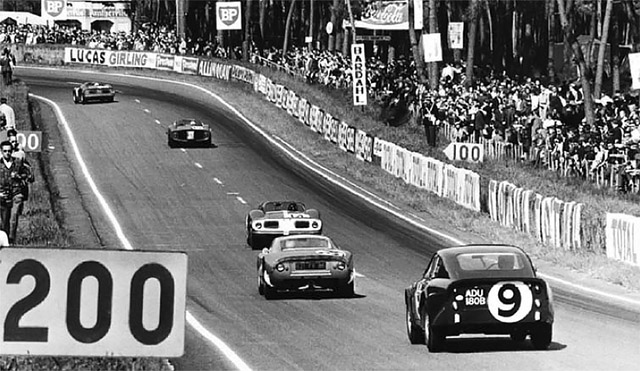

Below: Procter/Blumer car was quick, here chasing 904GTS of Buchet/Ligier and 330P of Hill/Bonnier in 1964, but crank broke after 118 laps. Bottom: England hares across the track for traditional-style start of final Le Mans Classic race.

This was a smart, coachbuilt (literally, by Worthing-based bus builder Harrington) coupe based on the Series II Alpine. At its first attempt, Rootes – cruelly, it would turn out – hit the jack-pot, snatching the Index of Performance from under the noses of the French Panhard brigade and the more race-orientated Lotus Elites. Despite two further attempts, this would be the Alpine’s sole success – indeed its only finish.

The V8 Alpine project had been signed off by the Rootes hierarchy by mid-1963 and subsequently some form of sporting activity was duly factored in as part of the company’s launch plans. In the US – the production car’s target market – Americans were becoming increasingly familiar with ‘Lee Mons’, in the main due to the achievements of the nation’s drivers there, so it made perfectly good sense to build a car – or cars – to contest the event. From then on, sadly, the quality of decision-making was somewhat lacking.

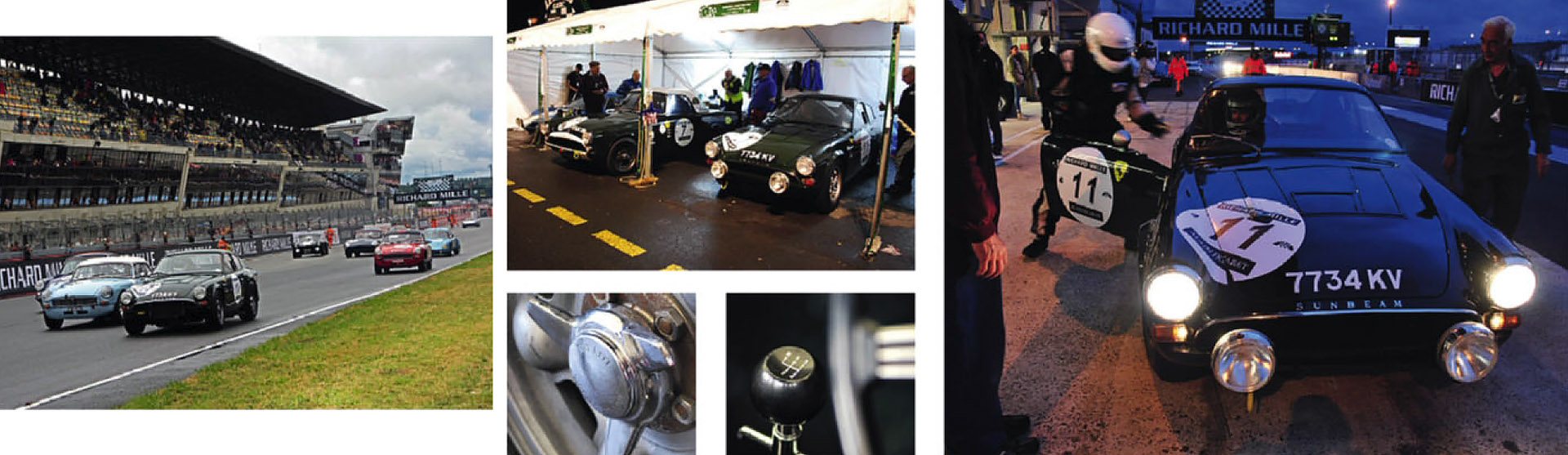

Clockwise, from above: fettling the works racers at comps department prior to the 24 Hours; night swap from Wall to England; T-10 four-speed ‘box; Dunlop knock-ons; in paddock, with Le Mans Alpine; England slithers away at start of fraught final Plateau 5 contest.

It didn’t help that the man initially charged with making it happen, Norman Garrad – father of Ian, whose enthusiasm had, in effect, made him the creator of the Tiger – left the competition department in February 1964, two months before the first test in France. His replacement was Marcus Chambers, who, to put it mildly, was horrified by what he found. He recalled in 1980: “The management had laid down that the cars were to be built on an Alpine monocoque, which was in turn the basis of the new Sunbeam Tiger. This and the fact that they were to be designed, built and tested in less than a year, imposed a terrible handicap on the whole project.”

Brian Lister, with his experience of large-bore sports cars, had been contracted to build a proto-type and two racers. Straight away, he voiced what every race fan would think – if we’re running in the prototype class, why not build a spaceframe and put it under an alloy rendition of the body, thus saving weight and enabling the use of better suspension components?

Rootes firmly refused and so the competition department began its journey with one arm tied behind its back. The irony is that the race cars – with their broader, Kamm-tail behinds, canted windscreens, fastback roof and 15in wheels – weren’t that recognisable as Tigers. In hindsight, this was possibly one of the few bonuses.

The shape was the work of Rootes’ in-house stylist Ron Wisdom and, although reasonably attractive compared to the low-slung Cobra Daytona or Bizzarrini, it looked too tall and too short in length. Even worse was the estimated 20% weight penalty over the standard model, making the Tiger the second-heaviest car in the 1964 race at 2706lb: 160lb more than the Daytona.

As if all of this wasn’t depressing enough for Chambers and Lister, the 4.2-litre (260cu in) V8 that had been bought from Ford for the production Tiger had already been superseded by a larger 4.7 (289cu in) unit, which in race trim meant a shortfall of 100bhp. But Rootes was committed to the smaller engine. To rub salt into the wound, the more powerful lump required exactly the same installation space, so cooling and access would have been no different. With little or no experience of V8s, the competition department had to source its 260cu in race engines from Carroll Shelby, the same guy who was running 289 motors in his cars…

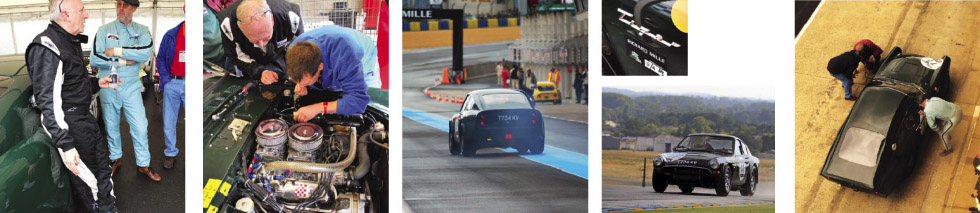

Above: England and Balme compare notes; Balme’s practice time was impeded by flailing anti-tramp bar, clouted when he took avoiding action. Right: key fob bears famous Talbot emblem; England pits for mandatory 60-second stop. Below: Lister with Elan and Mini Marcos in collecting area.

And yet, despite all of these encumbrances, by mid-March Lister and his small team had a running prototype registered 7734 KVJ the very car that we’re taking back to Le Mans. It’s widely accepted that this is also the first ‘Tiger’ built in England and was AF1 (Alpine Ford), which in turn became Project 870- the test platform for the proposed production version – before being handed over to Lister. It wasn’t referred to as such initially, but these days the original racing coupe is known in Sunbeam circles as ‘The Mule’, and was used extensively as a development hack until Le Mans – the two race cars being untested before their arrival at La Sarthe.

From the outset, it was obvious that the car had issues. A brief shakedown at Mallory Park three days before the Le Mans test had revealed that the handling of the future Tiger (it was briefly known as the Thunderbolt at that point) was far from ideal. While in France, both drivers – Peter Procter and Keith Ballisat – were critical of just about every aspect of the vehicle.

After exchanging pleasantries with Chambers, ex-Rootes engineer Mike Parkes – who was also at the circuit with his new employer, Ferrari – found himself taking The Mule for a spin.

“One lap was enough for Michael to confirm everything that Keith had said,” remembered Chambers. “Oil surge, axle tramp, poor brakes and overheating – and a Parkes lap of 4 mins 26 secs against a Ferrari time of 3 mins 47 secs.”

On further outings back in England, the team experimented with damper and spring rates, along with moving the rear Panhard rod and upgrading the front anti-roll bar. Although these all helped, misgivings about the car continued right up to the eve of the race when the number 8 Tiger ran its main bearings after qualifying. Chambers suggested to Rootes that it withdrew gracefully but, again, he was overruled.

Subsequently, both Tigers had retired within nine hours – a broken piston after three hours in car number 8 and a broken crank in number 9. Neither looked in danger of troubling the time-keepers or trophy engravers, 18th being the highest position that either achieved.

Tigers on track

The two ‘production’ racers – registered ADU 179B (number 8) and ADU 180B (9) – were driven at the 1964 Le Mans by Keith Ballisat/Claude Dubois and Peter Procter/ Jimmy Blumer. They were virtually identical to The Mule bar the rear valance, quick-jack lifting brackets and front wing vents. Unlike the prototype, though, there was no facility to get hot air out through the bonnet.

All three ran 260 V8s fed by two four-barrel Carter carbs, each rated at 460cfm, which was probably drowning the 4.2-litre motor with fuel. It wasn’t until Des O’Dell arrived at Rootes that the works got a handle on the small-block Fords, and it’s telling that none of the rally cars ever ran more than one four-barrel carburettor.

Rootes had the technical nous, but just didn’t have the time to deploy it. Works engineer and driver Bernard Unett was loaned 180B (179B was sold at the same time as 7734 KV), which became competitive during 1965 against the E-types, 250LMs and 26Rs with his development. Needless to say, he ran the bigger 4.7-litre engine but he also revamped the rear set-up using parallel links and wider tyres.

It was raced at last year’s Goodwood Revival in the capable hands of Rob Huff and is the only one of the three coupes to reside in the UK, Tony Eckford having owned it for more than 15 years. ADU 179B lives in Orange County, CA, with Darrell Mountjoy.

‘The bar had been grinding against the track when I was on the redline in top’

Blame for the project’s near-inevitable failure was laid at the door of the V8s. As Chambers put it: “I had consulted Shelby before the race as to our problems, but he did not want to offer any advice and was hardly polite when we asked for some help, a curious attitude to take to a customer who had just bought four special race engines.”

He concluded: “Brian Lister was probably more disappointed than anyone else. He had put so much effort into the whole thing and felt that it reflected on his judgement, but we were really on a hiding to nothing from the start.”

Fifty years later, could we better the efforts of the factory? There were no longer concerns about the motor because half a century of racing and development has led to professional builders supplying far more reliable units, although race-prepped 260s are still not that common.

Lack of regular running in historic events meant that ‘The Mule’ was also pretty unsorted and – after an exacting and meticulously accurate restoration – 7734 KV brilliantly reflected the car that the works drivers had encountered back in April 1964. It has been owned by staunch Tiger enthusiasts Chris and Lorraine Gruys for the past 11 years. They were keen to see it return to Le Mans in its anniversary year, so with the help of drivers Gordon England and Rich Wall – plus a stint from yours truly – they duly shipped the car from their home in the US.

Abrief sortie at Snetterton demonstrated that the car was hugely underdeveloped, yet this served us well because our approach to the event became much less ambitious – finishing being the only true objective. The handling was the primary beef: carrying any speed into a corner led to massive understeer, which immediately flipped to oversteer – sometimes even before reaching the apex and often quite unexpectedly. Coupled to an inconsistent brake pedal and an engine that faltered at 5200rpm, our work would be cut out around the historic circuit.

For the uninitiated, the entry for the Le Mans Classic is divided into six grids by age, with each group getting three 42-minute races over the 24 hours. It works well as a format because, if you do encounter a minor problem, there is a chance to fix it and not miss any track time. There are two qualifying sessions – one in daylight, the other in the dark. I’d elected not to drive at night – I’d done it 10 years ago in an Elan and it terrified the life out of me – so I got the lion’s share of the daylight practice, yet still managed to scare myself, not once but three times.

The modern part of the circuit is featureless and barren, a ribbon of grey running between wide-open gravel traps. These help to disguise a number of blind brows and corners, the black skidmarks on the track being the best indication of whether or not you’ve left your braking too late. Fumbling around trying to recall where everything went and reacquaint myself with the Tiger proved to be quite a challenge and I’d barely completed my first lap before adding to my problems. An ‘enthusiastically’ driven E-type dived up the inside at Indianapolis, only to start understeering towards my – read Chris and Lorraine’s – passenger door. Prudently, I took to the rumble strips but dropped two wheels into the gravel and knocked a bolt off the clamp that attaches the front end of an anti-tramp bar to the leading edge of the offside leaf spring.

What happened after Le Mans?

Marcus Chambers’ deputy, Ian Hall, used 7734 KV for the remainder of 1964, but it was sold via the Sports Car Centre of Northampton for £1450 in February 1965. The exact trail of its keepers over the following four years is unrecorded in the logbook, but it was raced several times again – initially throughout 1965 by Roger and John Eccles, who also installed a 4.7-litre (289cu in) motor. The Eccles (father and son) are thought to have last raced 7734 KV in a Redex Trophy round on 28 November 1965 at Brands Hatch, the event being the only known occasion when all three Le Mans Tigers raced together.

From the start of the ’66 season until April ’68, the car’s custodianship is unclear, mainly because it was ‘owned’ and used by racers and traders who didn’t feel the need to register their tenure with the DVLA. It may be that some hot shoes were merely loaned the Lister. The likely chain after the Eccles was Gerry Marshall, Jack Alderslade, John Pearson and John Scott Davies. During this time, 7734 KV was painted metallic blue with an offset white stripe.

Father and son Roger and John Eccles, here at Mallory Park sprint, raced KV several times in 1965.

Peter Wynn Jones bought the car – by then painted red – in April 1968. He certainly hillclimbed it but KV’s racing days were over, compounded two years later when its last UK keeper, Ronald Haig Kambourian, took the car to Wood & Pickett in London for a full interior and exterior makeover in a deep metallic burgundy colour. He said at the time: “The entire cost of the cosmetics was a ridiculous £2400, which was almost three times what I paid for it!’

In late 1972/1973, Kambourian advertised 7734 KV in Rood and Track and AutoWeek, and eventually sold it to a buyer in California – Dick Barker of San Diego.

Barker was to own the Lister Tiger until 2003 and was responsible for the car’s thoroughly researched and remarkably accurate restoration. Such were the lengths that he went to, it wasn’t until 1997 that the prototype was revealed to the public at that year’s Tigers United in Eureka, California, which is the only time that the two Le Mans race cars plus The Mule have appeared together since 1965.

The subsequent tinkling noise emanating from behind my seat was disconcerting but it turned to horror when I discovered that the bar had been grinding against the road surface for the rest of my laps, including three sections of the circuit where it was on the rev limiter (5800rpm) in top, at a speed in excess of 125mph.

A number of understeery/oversteery moments punctuated my time on the track, notably at the end of the start/finish straight, the chicane before the Dunlop Bridge and the Ford chicane where – even though I’d been advised not to – the car still wanted to cut across the kerbs irrespective of what I intended it to do. Nevertheless, despite being pre-occupied with looking after and wrestling with the car, it was an unforgettable stint and an incredible privilege to roar down the Mulsanne Straight in a Tiger built 50 years earlier specifically for the job. The image of Leo Voyazides’ red GT40 thundering by as we both passed the Hunaudieres restaurant will live with me for ever.

From top: Bradfield spotted the loose rocker- box bolts; Tiger burns spilt oil as it storms out of pits; kicking up dust towards Dunlop Bridge; mission accomplished – a relieved and delighted England reaches the finish!

Two of the Tiger’s three races were in the dark and the last was in drizzle, on what had become a treacherous surface. The poor old Mule was also starting to carry some minor mechanical mala-dies. A rocker on the motor had snapped after the first race – a result, we suspected, of the valve springs being too strong. Thankfully, there were no other component casualties in its demise and replacing it took less than half an hour. Unfortunately, one of the covers removed to carry out the repair didn’t seat properly and in the second race – in the early hours of Sunday morning – an increasing amount of smoke filled the cockpit.

It was a tense time at the end as we waited for him to reappear, but reappear he did.

Fortunately, it wasn’t enough to prevent a finish and was quickly rectified back in the paddock. So there was just the final race to complete.

From top: Tiger roars past the start-finish grandstand in the early hours of Sunday morning; England pits after just a lap of final race, fearing a terminal oil leak, but it was diagnosed as a couple of loose rocker-box bolts.

Gordon took the start, but was into the pits after only one lap and looking to retire the car. The Tiger was still smoking and, with the track being slippery enough without our car adding its oil to the mix, we pushed it into the garage. Feeling deflated, most of the team headed back to the paddock, but Christian Bradfield (competition secretary of the Sunbeam Tiger Owners’ Club) cleverly noticed that the car hadn’t dropped any oil in the three minutes that it had been standing. A rocker-box bolt or two were found to be loose and there were still traces of oil on the exhaust manifolds, but the engine wasn’t bleeding. Two minutes later, Gordon had re-joined the fray.

It was a tense time as other cars crossed the line and we waited for him to reappear, but reappear he did. For myriad reasons – not least history and the sheer hell of it – we somehow managed to contrive a highly unlikely result and take the chequered flag at Le Mans in a Sunbeam Lister Tiger coupe, exactly 50 years after the Rootes effort had so spectacularly failed.

Thanks to Gordon England; Chris and Lorraine Gruys; Christian Bradfield and the STOC.